Interview with Zélie Durand, Director and Animator of Stop Motion Short Film, "Sahara Palace," Incredible True Story of Loss, Dreams Unfulfilled, and Middle Eastern Cinema

|

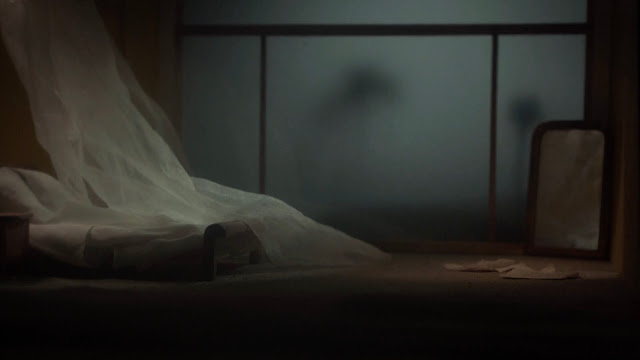

| A ghostlike apparition in a scene realized from Hedy Ben Khalifat's "Sahara Palace" script in Zélie Durand's Sahara Palace. Source: Vimeo. |

“The only things my grandfather left behind were dozens of 35mm film reels in my grandmother’s basement, which ironically took up a lot of space compared to the fact that nobody seemed to talk about him, and that he was noticeably absent of every family album,” Zélie Durand, a French director and illustrator, tells Stop Motion Geek about the very personal tragedy that inspired her most recent film, Sahara Palace – a transcendent, nine-minute long stop motion short film that realizes and further explores the greater themes of an unproduced film script entitled “Sahara Palace,” as well as the life and legacy of the script’s screenwriter: filmmaker Hedy Ben Khalifat, Durand’s grandfather, a man she never met.

“I was not allowed to touch the reels,” Durand continues. “When I started to ask questions three years ago, my uncle gave me a suitcase he inherited from Hedy, telling me he had no idea what was inside. Right after that, I spent a week alone reading the three versions of Sahara Palace contained in the suitcase, among his old passport and a death certificate.”

|

| Interior of Durand's model of the Sahara Palace hotel. Source: Vimeo. |

Durand, the first person in her family to read the scripts, remarks that they gave her “the illusion” that she shared a complicity with her grandfather, for by that time she was already pursuing a career in filmmaking by attending he Cinéma d’Animation at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, as well as being a collaborator with Les Chevreaux Suprématistes on the production of several popular science films. Durand also admits that, understandably, “at that moment he was very present in my mind and I had many questions left unanswered so I was thirsty for more information.”

In the instant she started to read the Sahara Palace scripts, Durand began to uncover not only the story living therein, but also the heart, imagination, and soul of her grandfather, which, as Durand recalls, proved a search that demanded an immense amount of dedication and scrutiny. “I looked for him in every line, every handwritten note in the bottom pages. I had to draw conclusions from a script that was very cryptic itself, with mysterious characters and dialogues,” says Durand. “I knew that I was making up my grandfather from all of this, it was mostly my own imagination; and I liked that idea. I knew that even if later in my research I was brought to discover true events of his life that would make him appear more human to me, I had to preserve the feeling of an impossible encounter, and that had to remain the heart of my movie.”

|

| Ghostlike birds haunt Durand's model of the Sahara Palace hotel. Source: Zélie Durand's website. |

Sahara Palace begins with a physical presentation of one of Khalifat’s “Sahara Palace” scripts before suddenly displacing us – the audience – in a world entirely juxtaposed to the pristine pages of a script: that of “Sahara Palace” – a real-life luxury hotel in Nefta, Tunisia which acts as the centerpiece of Khalifat’s script, as well as that from which both Khalifat and Durand derived the names of their films.

Yet Durand’s vision of the hotel is utterly… other than that envisioned by Khalifat in the ‘60s, in whose day the hotel was a thriving luxury getaway for the greatest stars of Franco-Tunisian cinema such as Brigitte Bardot, Jean Paul Belmondo, and Louis de Funès. In sharp contrast with that idyllic appearance, the hotel as conceived by Durand reflects the state of the hotel, as it stands in modern day, which closed down permanently in 2008 after lack of upkeep and use – as a once-lavish destination, now nearly as barren in the wilderness, a wilderness which was once its appeal, as it offered its tenants such an enviable escape from stardom.

|

| A behind-the-scenes photo of Durand's model of her Sahara Palace hotel. Photo courtesy of Zélie Durand. |

Despite being modeled on the state of the hotel it now more closely resembles, ironically Durand neither visited nor saw any documentation of the real hotel until after she had built her own model – the model seen in the film – which she based on her “first impressions from the script.”

“While I was reading it, I imagined a majestic building lost in the middle of the desert, filled with red velvet armchairs, intimate yet mysterious,” says Durand. “I made a clear parallel in my head between this place and the way I imagined my grandfather.”

This, perhaps more than anything else, is emblematic of the film’s theme of a paradoxical “impossible encounter” – impossible in the sense that the film does invoke, defying all possibility, a kind of conversation – as the film itself is very clearly two halves of a conversation between Durand and her grandfather, with Khalifat’s contribution operating as Durand’s inspiration for Sahara Palace and Durand’s contribution being the life she breathed into the film, very clearly painting the two sides of the conversation: One side – Khalifat’s – is symbolized in images, singular moments from Khalifat’s “Sahara Palace” scripts, realized by Durand. The other side of the conversation – Durand’s – is symbolized by Durand’s narration and images documenting her study of her grandfather.

|

| Apparitions acting out a scene from Khalifat's script wander the wilderness on the edge of Durand's vision of the Sahara Palace. Source: Zélie Durand's website. |

Yet, even within this symbolism, Durand subtly draws attention to the paradox of the idea of an “impossible encounter,” for, although Durand does realize scenes from her grandfather’s script, she acknowledges that they are, in all probability, not exactly how her grandfather envisioned them, for she represents the characters as mere apparitions haunting the hotel in the disheveled state in which it now stands – ghosts to haunt the hotel’s “stunning view on the oasis, the empty swimming pool and endless corridors filled with sand” described by Durand. And yet, despite Khalifat’s “contribution” to the conversation portrayed as not entirely tangible, it is, nevertheless, there – “the feeling Hedy was somehow around me, like a ghost,” says Durand.

Only at the end of the film are the two halves of the film’s psyche merged, in a scene profoundly moving and gorgeously realized: It’s an instant where Durand herself filmed in live-action – representing her “side” to the conversation – holds miniature model of a mausoleum made for her grandfather – representing Khalifat’s contribution to the conversation – placing it atop a sand dune in a wilderness not unlike that which is slowly swallowing the real Sahara Palace. She leaves the miniature to the discretion of the wilderness, allowing the same fate to take it as took the hotel of her grandfather’s fascination and fancy.

|

| Zélie Durand walks away after having placed her miniature model of a mausoleum on a sand dune. Source: Zélie Durand's website. |

“After a year and a half working on the movie, I flew to Nefta, in the South of Tunisia to discover the real hotel,” says Durand. “Getting there was an adventure in itself, the Sahara Palace being out of business since 2008 and no longer open to the public (it is under strict surveillance). So when I finally managed to gather the authorization to get inside, it really felt like I had achieved something beyond the movie itself. It brought closure to the whole experience. Of course the remainings of the hotel made it clearer in my mind that I was pursuing something that didn’t exist anymore, but at the same time it anchored my work in reality. Also, the place was very impressive, with its stunning view on the oasis, the empty swimming pool and endless corridors filled with sand… For a long time I had the feeling Hedy was somehow around me, like a ghost, but at that moment it was all gone. I think I really buried him that day,” Durand confides.

|

| Zélie Durand animating on the set of her model of the Sahara Palace hotel. Source: Zélie Durand. |

In our interview, Durand discusses her passion for filmmaking, how it flourished from an early age, and how her discovery of her grandfather’s filmmaking aspirations have recolored her perspective on her own work and passion. She also tells us about her journey to discover as much as she could about her grandfather and how it informed the way in which Sahara Palace came to be realized. She also gives us an in-depth look at how she went about composing the film’s unique visual aesthetic, and how she worked with the film’s composer, Nevil Bernard, and the film’s sound engineer, Guillaume L’Hostis, to develop the film’s soundtrack and specific “sound.” You can read our interview below in full.

A.H. Uriah: Hello, Zélie! Thank you for doing this interview! It’s a pleasure! To start, has filmmaking been a lifelong passion for you, or did you only come to it later in life? How has your path in life led you to become an illustrator, co-producer of music videos, and filmmaker – specifically in the medium of animation?

Zélie Durand: At an early age, 6 or 7 years old, I asked to join a casting agency to act in movies, as a child. I have no idea why I came up with that. Thanks to my parents I did join an agency, and though I’ve never had big roles I went on a few film sets from age 7 to 14. I enjoyed it every single time, and I think I was most fascinated with the intense working atmosphere. At that time I would write in school papers that I wanted to become a filmmaker later in life. Meanwhile, drawing and writing were the activities I enjoyed the most. I was struggling to find the best way to express the images I had in my mind. I never thought too much about it but I guess that animation naturally became the meeting point of those passions when I started studying in art school after graduation.

|

| Zélie Durand animates on the set of her model of the Sahara Palace hotel. Photo courtesy of Zélie Durand. |

A.H.: How did discovering your grandfather Hedy Ben Khalifat’s script, Sahara Palace, help you to understand him, a man who you never had the chance to meet? How did your journey to understanding who your grandfather was proceed from that moment (finding his script) afterward?

ZD: The only things my grandfather left behind were dozens of 35mm film reels in my grandmother’s basement, which ironically took up a lot of space compared to the fact that nobody seemed to talk about him, and that he was noticeably absent of every family album. I was not allowed to touch the reels. When I started to ask questions three years ago, my uncle gave me a suitcase he inherited from Hedy, telling me he had no idea what was inside. Right after that, I spent a week alone reading the three versions of Sahara Palace contained in the suitcase, among his old passport and a death certificate. I was the first person of my family to read the scripts, and that gave me the illusion that I shared a complicity with Hedy. Of course at that moment he was very present in my mind and I had many questions left unanswered so I was thirsty for more information. I looked for him in every line, every handwritten note in the bottom pages. I had to draw conclusions from a script that was very cryptic itself, with mysterious characters and dialogues. I knew that I was making up my grandfather from all of this, it was mostly my own imagination; and I liked that idea. I knew that even if later in my research I was brought to discover true events of his life that would make him appear more human to me, I had to preserve the feeling of an impossible encounter, and that had to remain the heart of my movie.

|

| Interior of a room in Zélie Durand's vision of the Sahara Palace hotel. Source: Vimeo. |

A.H.: How did your discovery of your grandfather’s script develop into making a short film about your grandfather and his unrealized script? Can you tell us how you proceeded in developing the film – from conception to finished film – across the two years it took you to make?

ZD: The first step for me was to gather as much information as I could. After reading the script I managed to meet the woman he was living with at the time he wrote it. She provided most of what I know now, from the day he left my grandmother to be with her, to the day he died. They stayed together for ten years, so we were both very moved to meet each other. She showed me pictures of him, and we talked a lot about Sahara Palace and how he struggled with his disease when he tried to produce it. It was in many ways the project of his life. He told a friend before he died that if he couldn’t make it he would like a young filmmaker to take over the work. Everything seemed to fall into place: me finding the script, the emerging idea of making a movie about him, the unfinished work… Unfortunately she had a stroke a few weeks after our first meeting, taking with her what seemed to be the last remaining living part of my grandfather. I met other friends of Hedy in Tunisia shortly after this, they all gave me perspective on his life and personality. From the script and what they told me I started to see images in my mind, and I then began to shoot animation without a storyboard, only following my instincts. I had a vague idea of the structure of the movie but I wasn’t sure how long it was going to be. I only knew that I wanted to talk about my grandfather through the script and the place Sahara Palace because they all seemed to have the same destiny.

|

| Interior of Zélie Durand's vision of the Sahara Palace hotel. Source: Vimeo. |

A.H.: As you recount in the film, “The real Sahara Palace didn’t withstand time, nor sand either. It’s different from what I expected.” Can you describe what walking through the real “Grand Hotel Sahara Palace” was like for you? How did you then go about reconstructing it in miniature for your film, Sahara Palace – was your replica an exact miniature of the real hotel or were you attempting to capture the “essence” of it?

ZD: As a matter of fact, I built my version of the Sahara Palace before visiting the real place. My replica is solely based on my first impressions from the script. While I was reading it, I imagined a majestic building lost in the middle of the desert, filled with red velvet armchairs, intimate yet mysterious. I made a clear parallel in my head between this place and the way I imagined my grandfather. After a year and a half working on the movie, I flew to Nefta, in the South of Tunisia to discover the real hotel. Getting there was an adventure in itself, the Sahara Palace being out of business since 2008 and no longer open to the public (it is under strict surveillance). So when I finally managed to gather the authorization to get inside, it really felt like I had achieved something beyond the movie itself. It brought closure to the whole experience. Of course the remainings of the hotel made it clearer in my mind that I was pursuing something that didn’t exist anymore, but at the same time it anchored my work in reality. Also, the place was very impressive, with its stunning view on the oasis, the empty swimming pool and endless corridors filled with sand… For a long time I had the feeling Hedy was somehow around me, like a ghost, but at that moment it was all gone. I think I really buried him that day.

|

| Khalifat's script as seen in Sahara Palace. Source: Vimeo. |

A.H.: In the animated scenes in Sahara Palace – where you realize sections of your grandfather’s script as well as scenes of your own conceptualization – the visual aesthetic mirrors that of the classic cinema of your grandfather’s day, most noticeably through your use of filmic granulation and highly dramatic and stylized lighting. From a creative standpoint, how did the idea for filming and color grading your scenes in this way develop? From a technical standpoint, how did you go about creating this aesthetic and what were your cinematic references and inspirations for it?

ZD: I do have a personal taste for dramatic lighting, I always seem to start creating by feeling an atmosphere and finding ways to transcript it into images. To me, all this work of research and digging in the past is strongly associated with atmospheres, whether it’s the basement of my grandmother, the houses of the people I met, or the descriptions of the hotel in the script. And this is how I designed the aesthetic of the movie: I had a very clear idea of what it had to look like, but in a more emotional than rational way.

I made almost everything by myself, I was helped for the construction of the sets, and had a few advices for the lighting, but I mostly spent all the filming process alone. I remember spending days searching for the right angle and the right light, shooting it and starting over if I didn’t feel satisfied with the result. I still think now that some scenes could have looked better, but you have to know when to stop. I had a lot of pressure because I was working on something that mattered to him, and was probably going to matter to my family afterwards.

|

| A close-up shot of the sand-swept interior of Zélie Durand's vision of the Sahara Palace hotel. Source: Vimeo. |

I watched a lot of metacinema movies at the time, like 8½ by Fellini, and movies about hotels, like Last year in Marienbad by Alain Resnais. I had the chance to ask what was Hedy’s favourite movie of all time, which is Peter Ibbetson by Henry Hathaway, a dreamy movie with beautiful scenes. I think it all influenced me…

A.H.: The sound design and musical composition for Sahara Palace are quite beautiful, moving, and excellently engineered. How did you and your associates on the film go about designing the sound design and musical composition for this film? How involved were you in this process?

ZD: I knew I wanted a musical composition with a strong theme, like the movies of my grandfather’s days. I was thinking about François de Roubaix and also the soundtrack of the 400 blows. I wanted the music to sound mysterious and bewitching, and I trusted the composer (Nevil Bernard) to start from that idea to develop his own ideas. I was very satisfied with the result, we made a few changes to fit the narration but it was mostly done on the first try. I then worked with the sound engineer (Guillaume L’Hostis) to lay the foundations of the sound design which he balanced later by himself… They were both very involved in my project, so it was a great working atmosphere.

|

| A sand-swept chair in the desolate Sahara Palace hotel. Source: Vimeo. |

A.H.: You mention on your website that, “My film revives stop motion passages in his script, and draws a parallel with my own discoveries about my grandfather. The heart of this project is an invented transmission, an impossible dialogue.” How did you select the sections of the script to portray in your film that you did (e.g., the man smoking a cigarette, the man playing cards by himself)? Were they the most analogous to your grandfather and what he meant to this story?

ZD: I selected the sections that I felt echoed my own research. “The man smoking a cigarette” is one of the most mysterious characters in the script. He seems to know that he is acting in a movie, he never interacts with the other characters, and nobody knows who he is. He appears and disappears several times during the plot, like a ghost. I immediately thought that he stood for my grandfather (who by the way was a heavy smoker). His former girlfriend confirmed that idea by saying that he probably would have played the part… The man playing cards is another mystery of the script, he appears two times, always playing “with an invisible partner”. I identified myself with this second character, trying to interact with someone who isn’t there. It also made me think about my grandfather when he left my grandmother, keeping his card set hidden, leaving the “game”… There are many possible interpretations of this character.

|

| A ghostlike man smokes a cigarette in Sahara Palace, realizing a scene from Khalifat's script. Source: Vimeo. |

A.H.: How has your discovery of your grandfather’s interests and ambitions of his being a filmmaker changed your perspective on your own work as a filmmaker? Moreover, what did it mean to you personally to actualize some of your grandfather’s script, which he never had the chance to realize?

ZD: As a young aspiring filmmaker, discovering my grandfather’s cinematic past has definitely inspired me to fully engage in this field of work. When he was young, Hedy was caught in the midst of a very mythical chapter of French cinema, and befriended some of the great filmmakers I truly admire. I look up to him because he was genuinely passionate about cinema. Choosing to adapt his script after his tragic death felt like fulfilling a dream of his, as well as establishing a link between him and I through something we both have in common even though we've never crossed paths, which is making movies.

|

| Sahara Palace title card. Source: Vimeo. |

You can explore more of Durand’s work by visiting her website and Vimeo.

Sahara Palace is not yet available to watch online in full. However, you can watch the trailer for the film by going here.

You can stay up-to-date with Stop Motion Geek’s upcoming interviews by subscribing to Stop Motion Geek via the “subscribe” button at the top right corner of our homepage, by following us on Facebook @StopMotionGeek, or by visiting https://www.facebook.com/StopMotionGeek/. You can also stay up-to-date with the blog by following us on Instagram or @stop.motion.geek.blog.

Comments

Post a Comment